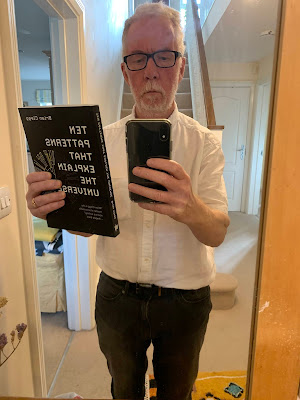

At one point in the talk, I put this photograph on the screen, which for some reason caused some amusement in the audience. But the photo was illustrating a serious point: the odd nature of mirror reflections.

I remember back at school being puzzled by a challenge from one of our teachers - why does a mirror swap left and right, but not top and bottom? Clearly there's nothing special about the mirror itself in that direction - if there were, rotating the mirror would change the image.

The most immediately obvious 'special' thing about the horizontal direction is that the observer has two eyes oriented in that direction - but it's not as if things change if you close one eye.

In reality, the distinction is much more interesting - we fool ourselves into thinking that the image behind the mirror is what's on our side of the glass with left and right swapped. But that's not really what's happening at all - something that is illustrated when you have a closer look at that photograph.

In it, I'm holding a copy of my book Ten Patterns that Explain the Universe (which is what the Royal Institution talk was based on). You can see the spine of the book in the image, on the side nearest the phone that's taking the picture. Now put yourself in the viewpoint of the mirror me. Holding a book like that, he is looking at the front of the book, because the spine is on his left. But I was looking at the back of my book, not its front.

What the mirror does is not swap left and right, but turn reality inside out like a rubber jelly mould, turning the back of my book into the front of the mirror book. In this process, by doing that same thing to, say, my left hand it makes it look as if it is the mirror reflection's right hand. But it's not - it's a back-to-front inverted left hand.

Welcome to the world of the looking glass.

Comments

Post a Comment